Pitch perfect: Last Chance U is the most honest portrayal yet of sporting hopefuls

Last Chance U: Laney opens in a nursery. A mountain of soft toys stands in one corner and an overhead night-light throws rainbow colours across a sleeping baby’s face. It’s not until several scenes in that we even see a football field. For the players of the Oakland Eagles, their world doesn’t solely revolve around sport. That kind of privileged one-track mind does not – cannot – exist in the world of junior college football we’re watching. Here, the game is not only a passion but a potential meal ticket, a means of escaping an abusive family, or a financial lifeline to support their children when they are barely adults themselves.

Across four seasons, Netflix docuseries Last Chance U has made a name for itself by providing outsiders with a direct line into the insular realm of college football. The Emmy-nominated show became just as popular among those familiar with the appeal of the pigskin as those who weren’t. Some of its success can be attributed to its deft narrative creation and expertly edited footage of game play. Mostly it’s because director Greg Whitley makes it clear from the outset that sport is only part of the parcel. That message is louder than ever in its final season – before the series turns its lens to basketball’s high-flyers next year – where match-winning touchdowns are overshadowed by powerful emotional displays.

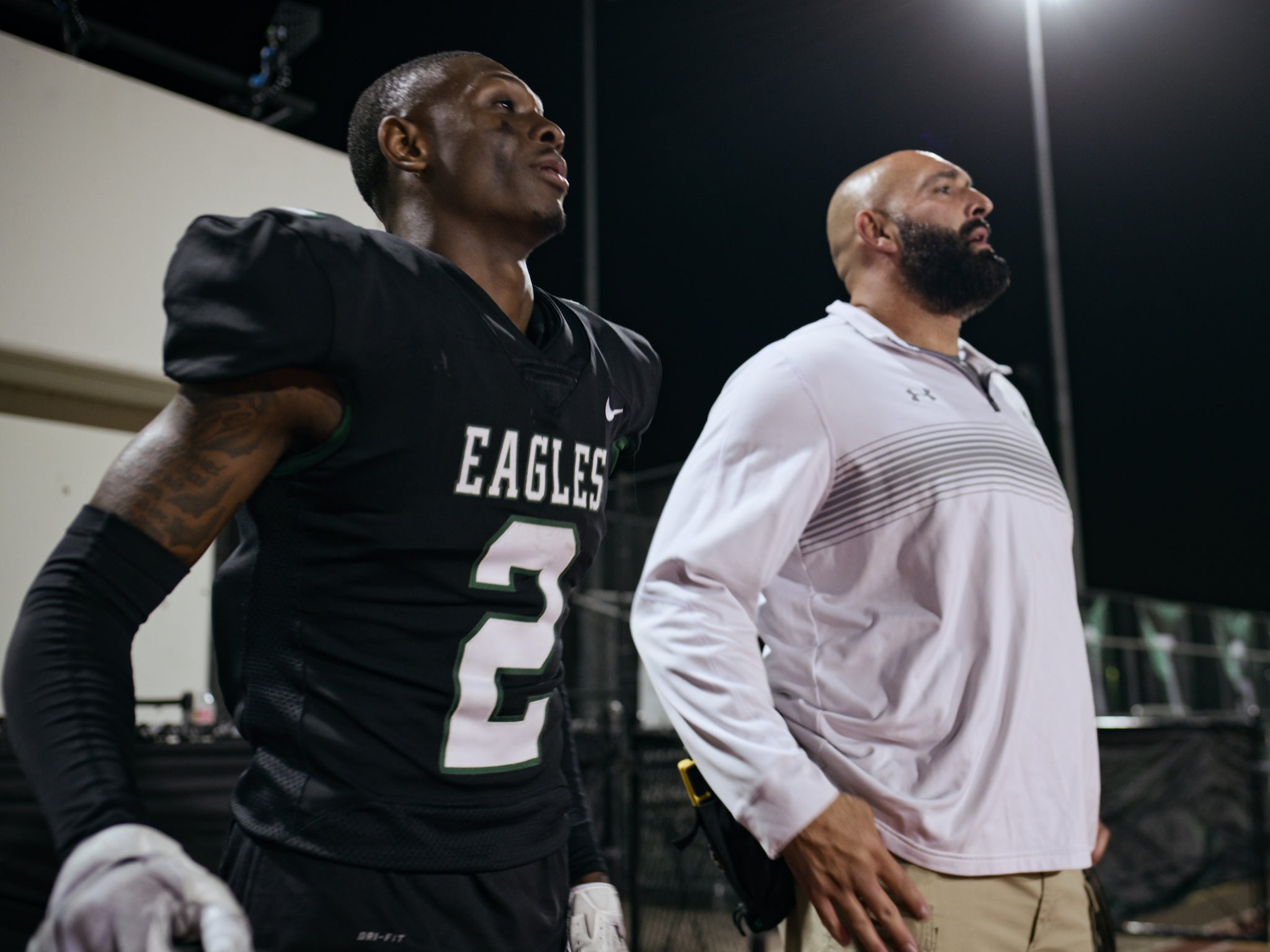

Using sports as a device to tell other, more intractable stories about class or race isn’t new: think Coach Carter, A League of Their Own or Bend it Like Beckham. Previous seasons of Last Chance U do it well, parsing broader themes through bingeable episodes of sporting triumphs and defeats. But by moving to Oakland, California, this show’s fifth season does it even better; it documents the Laney College Eagles as they enter a new season to defend their title as California state football champions. But the series takes a step back from the sporting action to delve more deeply into the plays happening off the field.

JuCo football has always had the makings of good television. It’s a last chance for young hopefuls who want to play at a higher level. Many of the players are Division 1 stars who have been booted out of their student-athlete programmes due to infractions like bad grades, drug use or skipping school. For them, JuCo is a shot at redemption. In this respect, the show follows a narrative that will be familiar to fans of past seasons: a cast of young, mostly Black athletes, who often come from childhoods of poverty and trauma, take a final Hail Mary pass at locking down a scholarship. Often it’s their one way out of bleak circumstances. By design, the stakes are high. But at Laney, where inner-city violence, racial tensions and increasingly unaffordable rent are monstrous obstacles, they are higher still.

Past seasons of the show were set on rural campuses where player prospects were similarly low, but in Oakland, a rapidly gentrifying city where many of the players cannot afford to live, the issues are magnified further. Laney is a community college; its student-athletes are not on scholarships and they are ineligible for benefits including on-campus housing.

For Nu’u Taugavau, the team’s 300-pound offensive lineman, taking this chance on himself and his talent has meant giving up his job as a Walmart greeter and having to lean on his wife for financial support – something he feels increasingly guilty doing. It means that without two incomes, they have to apply for food stamps to feed their two young children, the youngest of which is the baby in the show’s opening scene.

In the case of Dior Walker-Scott, the 5’8” linchpin for the team’s offense, committing to the Eagles means clocking 10 to 20 hours at the fast-food joint Wingstop after practice every day and sleeping in his car to avoid having to reconcile with a historically abusive father. Unable to afford housing in Oakland proper, some players, including Rezjohn “Ray Ray” Wright, must drive long distances in traffic to get to and from practice every day.

If previous instalments of Last Chance U used football to open the door to broader social concerns, this season finally crosses the threshold. There is an unswerving, steadfast dedication to represent life as it really is for these Laney athletes. In one scene, Walker-Scott is on the phone to his mum (who lives in Arkansas and calls him “cutie pie”) when she tells him she misses him and asks if he has enough food. He responds, “I miss you too mummy. Sometimes yeah, but some nights no because I don’t have money.”

The players’ unfiltered displays of vulnerability are surprising and touching, especially in the context of a sport that notoriously holds no space for feelings beyond fraternal bonds expressed through chest bumps and back slaps. It is no doubt in part due to coach John Beam: the grey-haired, green-tracksuited 60-something with a tan so deep you’d think it came from a bottle if it wasn’t paired with an accent so obviously Californian. Together with his assistant coaches (who knew American football necessitated so many?), Beam works day in, day out to transform these 90 individual athletic units into one well-oiled kicking, throwing, catching, tackling, hurdling machine. His racehorse work-ethic and love for the f-word, though, is where the similarities between Beam and his Last Chance U predecessors end.

Fans of the series will know that the figure of a despotic and sociopathically competitive coach has been a fixture in Last Chance U since the series began. In 2019 coach Jason Brown, the cigar-smoking hyper-aggressive braggart who appeared like something straight out of Full Metal Jacket, resigned after texting a German player on his squad, “I’m your new Hitler.” Every season bore renewed disappointment for viewers hoping for a coach’s redemptive arc; underneath all that screaming and bravado, there was no gooey centre after all – just more screaming. That’s not to say Coach Beam does not yell. Screaming, swearing and threats are still rife and Beam regularly loses his temper at the players, at the ref, at his assistants. Frustrated by a player’s inability to follow what he sees as a basic instruction, Beam tells him, “Grow your ass up. I guarantee I’ll rip your f****** nuts off if you f*** up on Sunday’s game.”

But Beam’s hold on the team is intensified by his sincere interest in each of his players as a developing person as well as a successful athlete. And for every threat to castrate them, the coach doubles down on his words of encouragement and emotional support. He is a rare breed of football coach. One that speaks about mental health and PTSD. He does breathing exercises and encourages his team to do the same. When an athlete is particularly struggling, he will sometimes refer them to his wife, a professional therapist specialising in services for people of colour.

Crucially, however, Beam is unafraid to shoulder some of that responsibility too. When Ray Ray is benched with a suspected broken ankle and begins to cry, fearful that he will have to sit out a crucial season on which his career hinges, Beam holds him on the sideline and repeatedly tells him, “I got you.” He kisses his forehead and grips his shoulders: “I love you, man.” And Ray Ray says it back to him.

What is most promising is how quickly Beam’s coaching style fosters a positive team culture. The players take responsibility for their mistakes on the field (“My bad y’all”), they voice each other’s praises (“I’m so motherf****** proud of you, man”) and pep each other up when the scoreboard is against them (“Where’s your f****** grit? Where’s your f****** heart?”). Where the lifeblood of past seasons has been the anger and aggression of larger-than-life coaches, this latest series derives it from a more intimate place; the player’s shared determination to overcome emotional and economic hardships and their die-hard commitment to supporting one another in doing so.

That’s not to say that season five lacks in dramatic slow-motion shots of a football soaring through the posts, nail-biting sequences of a scoreboard ticking up for the opposing team or the bone-crunching sounds of a particularly aggressive tackle. As usual, Whitley’s camera never misses its target on game day: these boys are rendered superhuman as they accomplish improbable feats in their very own hero costumes of shoulder pads and helmets.

But what is more impressive than the show’s ability to capture this fantasy is its willingness to shatter it in the next scene, and by doing so reveal a more human truth: these young men aren’t playing to win, they’re playing to survive. And their intense motivations to be on the field have little to do with football at all. More important to Taugavau than assisting a game-winning touchdown is converting his skills into diaper money for his babies. Sports documentaries are never actually about sport – Last Chance U: Laney is a blistering testament to that.

tinyurlis.gdv.gdv.htu.nuclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.detny.im